So This Finn and a Pole Walk Into a Bar...

Tuesday 02/06/2007 1:09 AM

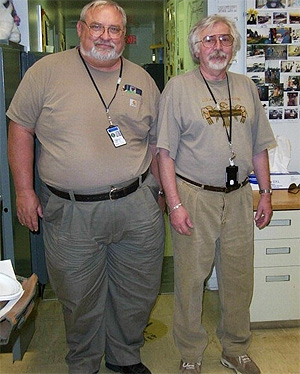

The infamous Jenny Craig picture. The little guy on the left (my dad) is your before and the fella on your right (George Wojcik) is the after. File Under: Dad; In Memorium; Photograph, Digital Manipulation/Composite; Someone Else's Image |

Yeah, I know. It sounds like the beginning of a bad joke. How I wish it was the start of a good joke, because we could use a little humor around here right now.

It is my sad honor to announce to you that one of my father's closest friends, George Wojcik, died Monday evening after far too short a battle with lung cancer. He is survived by his loving wife and family.

We've all heard about quantum physics, some even quantum mechanics, but so few of us really understand that word. A quantum is the smallest indivisible dollop of energy. The key is that word indivisible.

When you work at a place like Fermilab, where my dad and his buddy George worked, just about everybody understands what a quantum leap is. If asked, the rest of us would probably say, "Wasn't that a TV show a while back?"

When an electron jumps from one energy level to another it does so via a quantum leap. Remember how a quantum is indivisible? Well, a quantum leap is discontinuous. That's a fancy science term that means it disappears from over here (pointing close by to your left) and instantly re-appears way over there (pointing far away over on your right).

If you've never been exposed to these ideas, your head might be spinning a bit trying to accept these facts. Yes, energy has a smallest unit which is unsplittable beyond that point. And, yes, those little specks of energy jump around in ways that are reminiscent of the transporters on Star Trek.

By now you're probably thinking that my dad and his buddy George must have been a couple of highfalutin physicists or what not. No, no, no. They worked in the Alignment Group, which meant that whenever the physicists figured out what experiment they wanted to run, people like my dad and George had to make sure that the particle beams and such would be in the right places at the right times so the physicists could further scrutinize reality on all of our behalves.

People like my dad and George didn't dream up the experiments, but they did engineer and innovate as needed to make sure the experiments were possible.

I'm not sure when it happened exactly, but at some point, after God only knows how many of these projects, George and my dad took a shine to each other. George would go back home to Poland and return with bottles of Polish vodka for my dad. They'd work late together. They'd visit with each other's family. They were not just friends — they were intellectual partners, working together, challenging each other to do things the right way. To solve a problem wasn't just an item on a to-do list to tick off at the end of the day. For them, solving a problem was their way of reaching higher for some paragon of how they thought things should be.

I'm reminded of a passage from Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead:

Man cannot survive except through his mind. He comes on earth unarmed. His brain is his only weapon. Animals obtain food by force. Man has no claws, no fangs, no horns, no great strength of muscle. He must plant food or hunt it. To plant, he needs a process of thought. To hunt, he needs weapons, and to make weapons — a process of thought. From this simplest necessity to the highest religious abstraction, from the wheel to the skyscraper, everything we are and everything we have comes from a single attribute of man — the function of his reasoning mind.

I have a dream of an impossible moment. George and my father choosing to go back in time, to return to their youths simultaneously. Fair-haired eleven-year-olds on a farm somewhere. It's the middle of summer and time is more taffy than torrent. Up in the barn with the late afternoon sun breaking through the boards, you can see the dust they stirred when they climbed the steps up to the second floor, the hay loft, the basketball court. They sit cross-legged on the floor, ignoring the splinter threat, facing one other and they each hold up a thumb.

In this impossible moment they know what lies ahead, the burdens and distractions of adulthood, but that only makes each second sweeter. George takes out a large sewing needle and sticks it in his thumb. He squeezes until the blood is forced out in streaming drops. George swings the needle at Butchie's thumb, but my dad stops him and says, "I'll do it."

Once he's got his thumb leaking crimson just as well, Butchie sticks it to Georgie's. They press hard against each other trying to force the other back as their blood mixes and smears down their thumbs and across their hands.

In this impossible moment, just before it's time to return to the world of men and machines, they recite those words together, aloud: Man cannot survive except through his mind. He comes on earth unarmed...

No mere prose for them — these words are an incantation that would have had them burned at the stake centuries ago. These words are their blood oath to each other, but, more importantly, to themselves. Words of meaning not meant to conjure, but to inspire. Not to dazzle, but to remind. A transmutation from letters and words of ink on a page into air and vibrations, sounds spoken, uttered, and finally into energy running through their minds. Neurons, synapses, electrons.

And then they're back. Sitting at their desks at Fermilab. Just like those little bits of energy leaping about, there is no middle passage for either of them. Moments ago they were in the barn. And now they've returned. They are here. No map or trail of breadcrumbs to lead them back to that juvenile rite in an old barn on a forgotten summer afternoon. Like two men could ever form such a bond of respect and understanding and connectedness.

Then I think of George and his buddy, Stu. Like two men that could ever form a bond of respect and understanding and connectedness.

Only now that bond is different. Now it is a thin silver chain connecting them in dream. Now we have, unfortunately, a very possible moment to contend with. One of them has leaped ahead. And there is no way back.

Dad, I'm so sorry you've lost your friend, George. I know you loved him and respected him. My knowledge of your sadness pains me all the more. You were just getting accustomed to this whole retirement bit and I know that somewhere in your mind you looked forward to spending more time with George, especially once he retired. Working together with him not "on the job", but on the rest of your lives. Phone calls, car trips, visits to each other. I am so sorry that's gone for you now.

Dad, I'm going to end this. Not with my words, but with yours. I have two sheets of lined paper with block lettering in pencil that I've treasured for years. They are sealed in protective, plastic sleeves and they are always within arm's reach of me. I almost showed them to you when you were here last April, but I'm not sure why I didn't.

Well, yet another secret no more.

You wrote something a long time ago. The title is FAREWELL and it is addressed to your friend Jon. This is how it ends:

Why do I miss you now?

You were just a man... but

There was manner or a style or a way

About you.

I hope you're happy, where you are.

I don't know where

I do know I am still

Influenced by your teachings.

Permalink | Comments | Trackback